Interactive Robot (Mirrly)

Problem Definition

- Hired to create a humanoid, child friendly robot for in the future to be used for studying children’s interactions with robots for therapy purposes.

Goals

- Have a fully functioning robot that can be handed off to the lab for researchers to use which includes a fully finished mechanical and electrical system integrated together.

- The robot should use off the shelf controllers like an arduino and raspberry pi.

- The appearance should be friendly and “toy like”.

- Sensory inputs and outputs like capacitive touch sensors, cameras, touch screen, speakers, and microphone should be integrated.

- Functionality:

- Detects facial expressions with camera

- UI with touchscreen

- Edge detection to prevent falling off tabletops

- Have neck and eye motion

Roles and Responsibilities

- I conducted all the mechanical design in Solidworks, procurement, and assembly in the shop which included using hand power tools.

- I did the full electrical design including

- Selecting sensors, motors, and other hardware.

- Creating schematics, and PCB layout

- Designing the PCB and its components around the mechanical chassis.

Technical Approach and Design:

Step 1: Mechanical Design

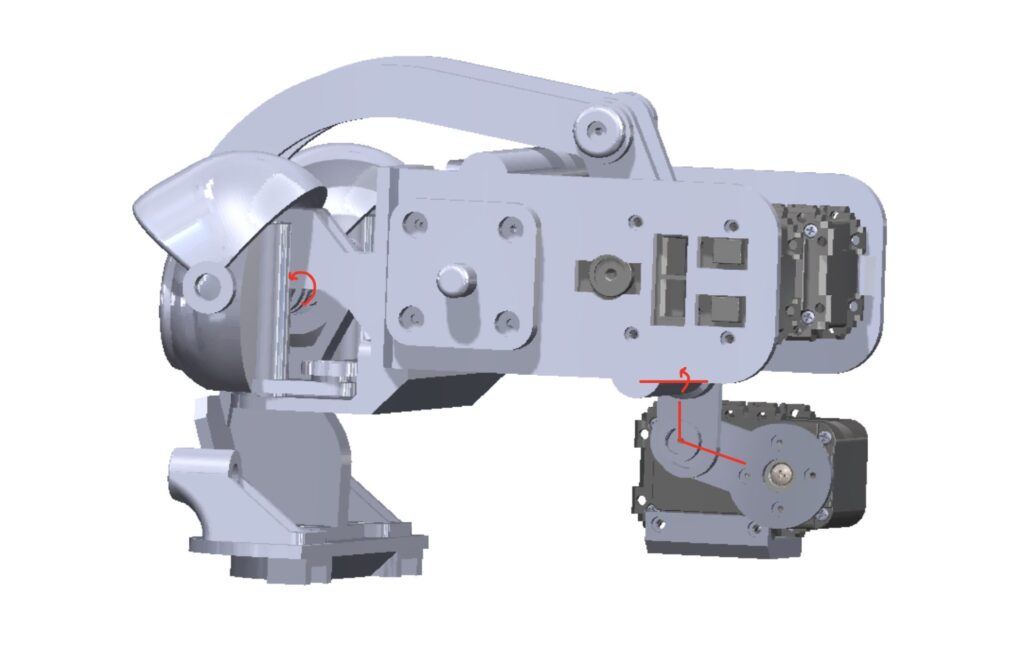

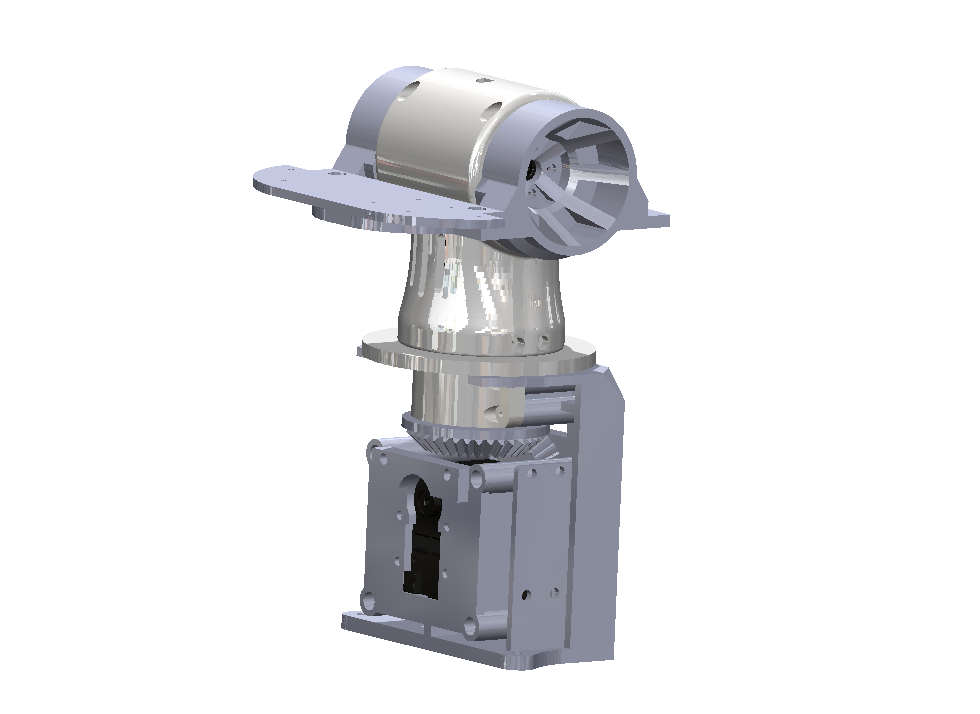

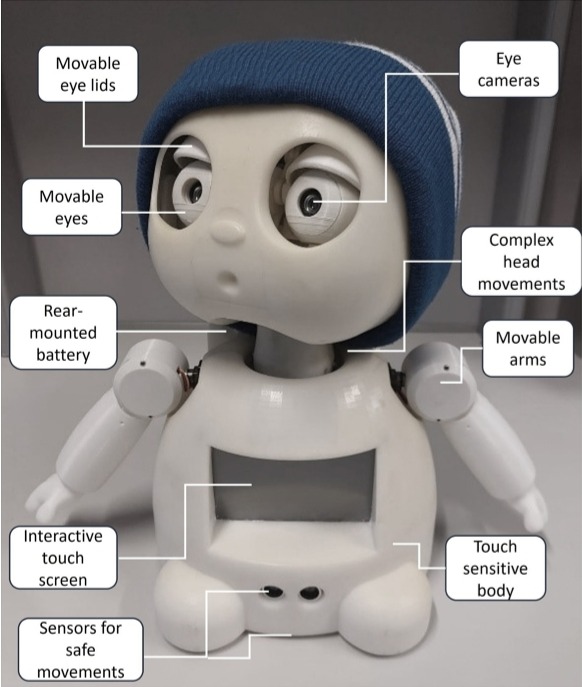

Neck and Head Design

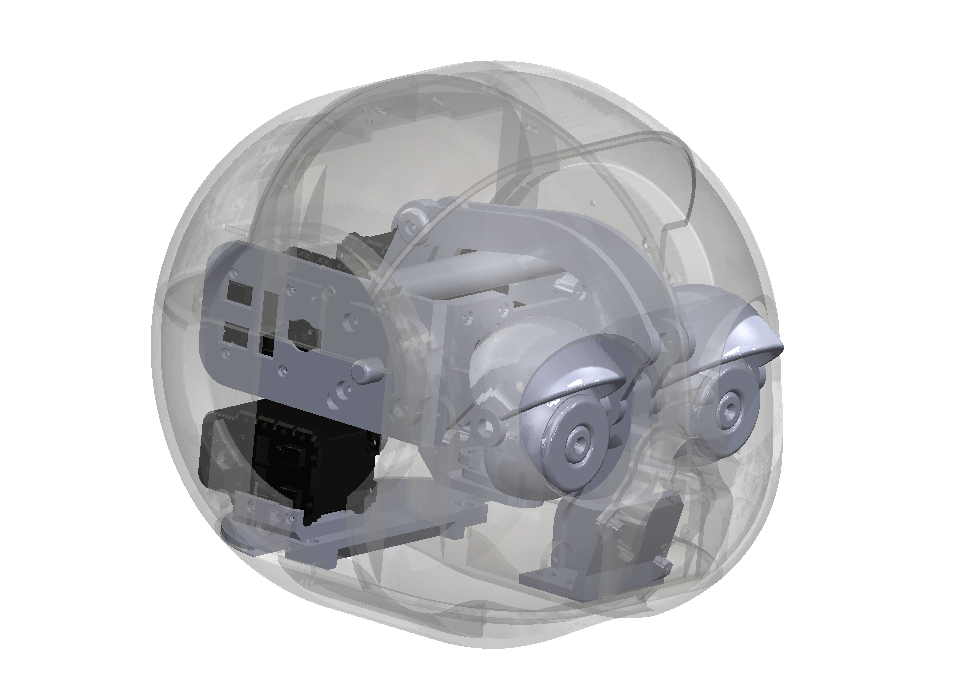

The neck and head are the most important aspect so this was done first to design the body around. I took inspiration from other toy like robots and developed the following design.

Defined the relative size of the head and shape to conform the internals around.

Identified the movements / functionality of the eyes.

1. Eyes should move to side to side and up and down in unison.

2. Eyelid should move up and down individually (should be able to wink).

- 2 curved links are attached to the eye lids to individually move them with seperate motors.

- The rear motor uses a rod to rotate the entire unit for moving the eyes up and down.

- A motor rotates and drives a liner shaft side to side to rotate the eyes.

Body Design

Body was designed to have appropriate proportions and a good appearance.

Step 2: Motor Selection

Robot is weighed ~ 9 Kg.

MG90 servos were used for the shoulders as these were in stock and I was told to use them.

The AX-12 Dynamixel Servos were used for the Head and Neck because the lab had these in stock.

Step 3: Electrical and Controls Design

Sensors and Components

Capacitive touch (I2C), ultrasonic (UART), TOF (I2C), accelerometer (I2C) motor driver (PWM), MG90 servos (PWM).

Arduino MCU is selected to control these because they demand precise, real-time I/O that Linux can’t reliably guarantee.

- MG90 servos need rock-steady 50 Hz pulses with microsecond-level stability—Linux task scheduling jitter (especially while the Pi is busy with the webcam/audio or filesystem) makes servos twitchy and motors jerky.

- Ultrasonic ranging relies on timing an echo pulse with microsecond resolution; on a Pi you’ll miss edges or block the CPU with ugly busy-wait code.

- I²C sensors (capacitive touch, ToF, accelerometer) expect deterministic polling/interrupt handling and sometimes clock-stretch; under load the Pi can delay transactions, collide with other drivers, or hang a shared bus

An MCU gives hardware PWM for servos/motor driver, input capture for ultrasonic timing, interrupt-driven UART/I²C with minimal latency, and a watchdog for safety—so sensing and control stay smooth even when the Pi is busy.

Eye cameras, microphone, speakers, touchscreen, dynamixel AX-12.

A raspberry pi is selected to use these components because Linux and has the drivers, bandwidth, and libraries these peripherals need.

Webcam: UVC cameras + OpenCV/GStreamer need USB bandwidth, large buffers, and a filesystem; most Arduinos aren’t USB hosts and don’t have the RAM/CPU to stream video.

Microphone & speakers: ALSA/PipeWire handle audio capture/playback, mixing, resampling, and USB/I²S sound cards

- Touchscreen: The Pi provides a frame buffer/GPU and input stack (DRM/KMS, evdev, Wayland/X). An Arduino can drive only very simple SPI displays at low frame rates and has no real GUI toolkit.

- AX-12 Servos: AX-12s speak half-duplex 5 V TTL serial (Protocol 1.0); the U2D2 handles the electrical/half-duplex details and presents a plain USB serial device to Linux.

If you tried to use an Arduino for these, you’d run into missing drivers/USB host support, severe RAM/CPU limits, choppy video/audio, painfully slow UI rendering, and lots of custom firmware just to match what the Pi gives you out of the box

Raspberry Pi <-> Arduino: Connected via USB, and the Arduino is treated as a peripheral.

Big Picture

Pi (Linux, Python/C++) = perception, UI, audio, high-level control, Dynamixel bus master, and the one talking to the Arduino.

Arduino (C/C++) = tight motor control + precise I/O: PWM (motors & MG90s), encoders, ultrasonic timing, I²C sensors (touch, ToF, accel), UART sensors, watchdog.

Battery Selection

- Power budget maximum of 3.63 A (5V)

- 3 A (11V)

Ovonic 50C 11.1V 2200mAh 3S LiPo Battery Pack

5 V rail: 3.63 A × 5 V ≈ 18.2 W (from a buck regulator)

11 V rail: 3 A × 11 V ≈ 33 W (direct or via a high-efficiency regulator)

Total ≈ 51 W. From an 11.1 V (3S) pack that is only ~4.6–5.2 A from the battery

Discharge capability. A 2200 mAh, 50C pack is (theoretically) good for ~110 A continuous; even assuming a much more conservative 10–20C real-world capability (22–44 A), the ~5 A average and higher motor/servo peaks are easily covered.

Battery Life

Idle / sensing (Pi ~0.9 A @ 5 V, tiny 11 V load ~0.2 A): ≈ 7 W total → ~2.8 h

Ex calc: I5V = 0.9A, I11V = 0.2A. Runtime = battery Wh / (average power at battery (W))

Mixed driving (Pi ~1.0–1.2 A @ 5 V, two DC motors averaging ~0.6 A each @ 11 V): ≈ 19–20 W → ~60–65 min

Light cruise (Pi ~1.0 A @ 5 V, motors ~0.8 A each avg): ≈ 23 W → ~50–55 min

Aggressive (Pi ~1.2 A @ 5 V, motors ~1.0 A each avg): ≈ 29 W → ~40–45 min

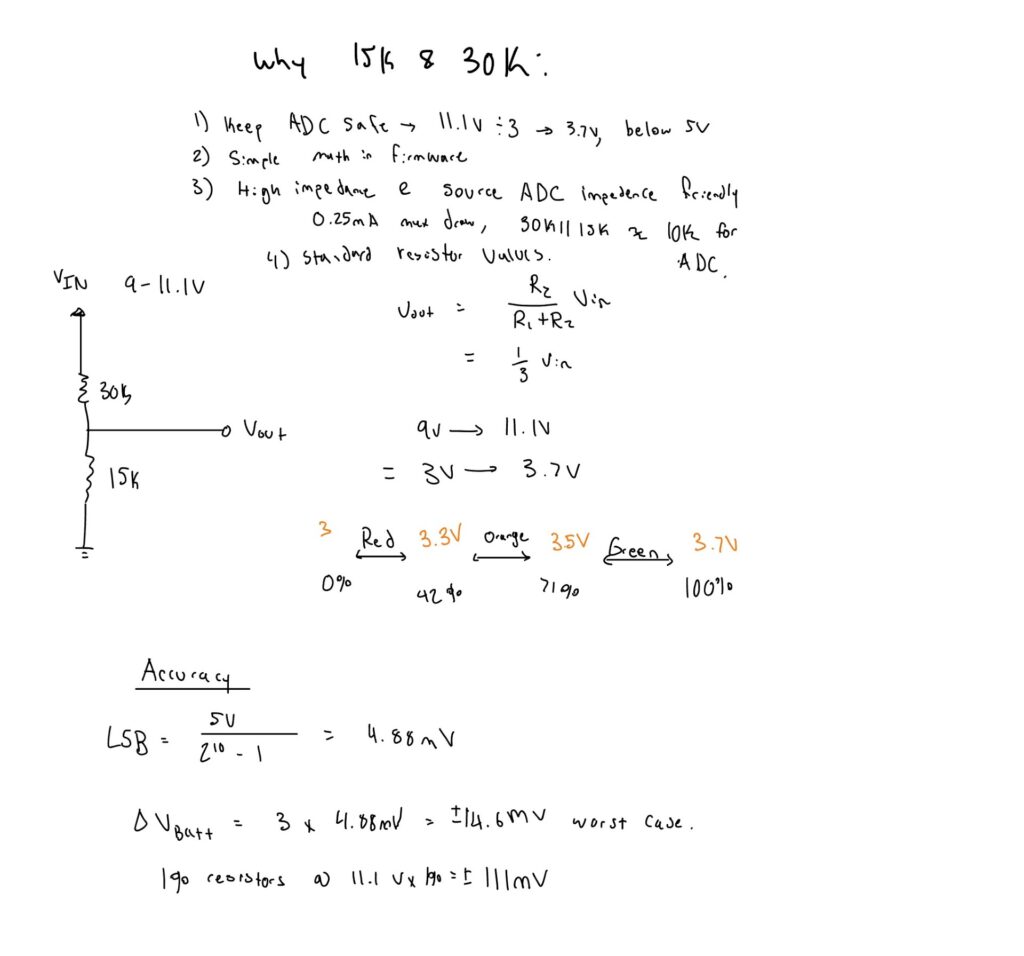

LiPo batteries are easily damaged when over discharged past 9V.

A low voltage cutoff switch is added as a component to turn off system past 9V.

Buck Converter

Manager wanted a pre made unit as these are tested and confirmed to work.

LED Battery Monitor

Block Diagram

Schematic Design

PCB Layout

PCB Mechanical Stackup

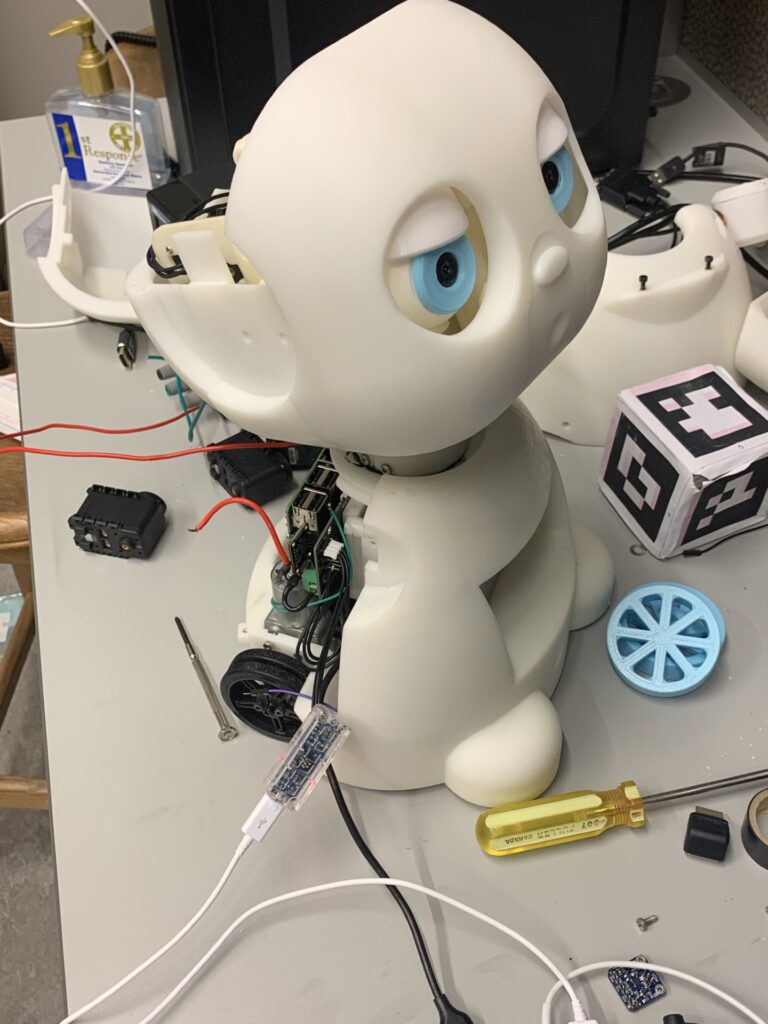

Step 4: Electrical Prototype Assembly and Initial Firmware

- Developed firmware for all sensors and actuators to confirm that the electrical system is functioning properly.

Finished Product / Results

MIRRLY is publicly announced by the University of Waterloo.

- Full system pass‑off — all sensor nodes and 8 actuators passed bench tests for I²C/UART traffic, PWM response, and fault‑free operation over 24 h burn‑in.

- Battery monitor accuracy ±0.05 V — voltage‑divider readings matched a calibrated DMM across 0–11.1 V.

- Reliable edge avoidance — time‑of‑flight board stack detected 100 % of drop‑offs ≥30 mm in 50 tabletop trials.

- Peer‑review validation — hardware methods and data accepted at ACM HAI 2024 (36% acceptance rate).

- Educational impact — the finished robot served as the core apparatus for a master’s thesis and helped the student successfully defend and earn their degree in 2025.

Challenges

Things I would Change From New Experience